I’ve logged countless hours on Google Earth searching for and following abandoned railroads all across the country. For those who don’t mind losing many hours of spare time, it can be a fun and rewarding endeavour for history and rail buffs interested in such a facet of industrial archaeology. I’m sure it doesn’t give quite the thrill of urban exploration or jungle bushwhacking, but nevertheless it’s a very interesting hobby one can pursue from the comfort of one’s computer chair without any real risk or cost.

First things first, one would probably ask, “doesn’t Google Earth already have a railroad layer overlay?” Of course it does, and a very comprehensive one; it’s located under ‘More > Transportation > Rail.’ However, this overlay only covers active and extant railroad lines, or ones abandoned within the last several years that GE has yet to remove from its database. Abandoned railroads are completely unmarked on Google Earth (though OpenStreetmap lists many abandoned lines, apparently) and if one wishes to add them, one must manually do so by tracing them with the path tool or importing someone else’s KML files with abandoned lines marked.

Active NS (fmr SOU) line through Oakman, AL, is charted on Google Earth, but the abandoned wye at the center of the picture leading to an abandoned SOU branch to Corona Mine is -not- marked on any overlay.

While there are some resources available for those who wish to mark abandoned lines, for the most part it’s up to the user to find and follow abandoned lines. For most railfans, it should be rather easy to pick out the telltale signs of where a line once ran, but for others, particularly those as inexperienced as myself, it is helpful to have a few tips on how to locate abandoned lines in the overhead view that Google Earth offers.

For this short little article, I will mostly be using screenshots from abandoned lines in Alabama, my home state, as I’ve spent more time looking up things here than anywhere else. Most of these tips should be relevant no matter where the line you’re searching for is located.

First off, one should get used to using the Historical Imagery timeline slider, located on the toolbar. Reason being, while very recent images are usually of extremely high resolution – making the search for basically anything that much easier – the older images are not only closer to the date of abandonment (and therefore the landscape hasn’t been altered by time or development as much) but, generally being without color and in much lower resolution, also tend to be at a level of contrast that makes linear features such as rail ROWs stand out more.

Abandoned SOU line through Greensboro, AL. Images from 1992 and 2013; the ROW is much easier to pick out in the older image, as time has worn away some evidence in the 21 years between shots. The ROW is still very clear outside of town in the 2013 shot, though, so this is not always a perfect method of making ROWs easier to locate.

Another good layer to have on is the ‘Photos’ layer, from the sidebar. Many abandoned ROWs have photos along their length, generally posted to Panoramio then selected for Google Earth. If you’re following a linear feature and there are photos indicated along the length, check them out, and you stand a decent shot of the photos being of the abandoned rail ROW or an associated railroad feature that help confirm the presence of an abandoned line. Similarly, check to see if Street View is available for any roads that a possible ROW crosses.

Abandoned DeBardeleben Branch of SLSF crossed the road in Sumiton, AL; Street View helps confirm the existence of the ROW, as seen from the bottom left to the upper right-center. Subtle features, such as the tiny still-extant drainage ditch crossing under the ROW, can help confirm that this is an abandoned rail line as opposed to a power line cut or private driveway (which would typically be much narrower or use a more traditional culvert as opposed to this feature)

Before starting the quest for specific abandoned lines, one should obviously have some general idea of where the line that they wish to track was located. If one knows the name of one or more towns that the line ran through, for example, the search can be started in that town, or if the abandoned segment in question branched off a mainline in a certain county, one can look for evidence of said branch along the GE rail overlay in said county. That said, it’s certainly possible to search for abandoned lines quite randomly, with no particular intent, and hope to find evidence of abandoned trackage along existing lines. This does sometimes yield interesting results.

Unmarked short spur in 1999 imagery to a now-demolished feed mill in Jasper, AL; location now bears no evidence of rails branching off the main NS line here. Evidence of short industrial or agricultural spurs like this can be found frequently while searching historical imagery along existing lines.

Another important tip to consider, whether searching for an existing line or looking randomly for abandoned lines across the landscape: Follow water! Though railroads try to cross water as little as possible to avoid having to build expensive bridges, sometimes water crossings are necessary, and often bridge piers (or, if you’re lucky, extant abandoned bridges!) are the only remaining evidence of a rail line through a particular area. Bridge piers stand out in aerial imagery, even if the ROW is not visible on adjacent shores, and, if you’re browsing with the ‘Photos’ layer on, there will often be photographs of the piers, as such features are popular photograph subjects even to the non-railfan. One may also find abandoned road bridges by searching waterways, but at least in my opinion, such finds are worth the effort even if they don’t relate to railroad activity.

These bridge piers, dating to the late 1890s and abandoned by the 1930s, provide the only remaining evidence whatsoever of the old SOU branch to Masena, AL, from the now-abandoned connection to the main in Marvel. Discovered only by random searching of waterways, and confirmed by the associated photograph, I was able to find out a lot of fascinating information on a long-forgotten turn of the century coal hauling branch that once ran through this area that I had even no vague idea of having ever existed.

Another way – which would seem fairly obvious – to locate abandoned lines is to note where existing rails on the Google Earth overlay end, and visually check to see if there is abandoned ROW beyond that point. This is frequently the case.

Old L&N line from Attalla, AL to Birmingham is abandoned beyond a Tyson Foods facility near Ivalee, and thus the overlay ends here; however, the ROW very clearly continues SW, where it will pass through Tumlin Gap and Oneonta on its way to connecting with a former L&N main in Birmingham.

When checking towns and cities to locate abandoned lines, it’s often easy to pick out where the ROW runs by noting the alignment and arrangement of roads. To minimize the number of grade crossings that would have to be maintained and safety-fitted, there will be a gap in roads with only a few crossings where a railroad crosses through a populated area. This is often still evident many decades later, and to make things even easier, many roads which run parallel to a rail line – or are built over a ROW – are named ‘Railroad Street’ (or road, avenue, etc.) or, sometimes, a name befitting associated railroad infrastructure (Station Street, for instance)

Abandoned Central of Georgia line through Hartford, AL. Note Railroad Avenue, built alongside ROW. The ROW can be easily traced by following the gap in roads from NW to SE in this image.

Also, by use of the photo layer, one can often find old depots, which are popular photograph subjects.

Old Elkmont, AL, L&N depot. ROW here is marked by the light grey line of the hiking trail built on the railbed, and a closer zoom will show that the depot is on Railroad Street. Thus, the signs of a ROW here are unmistakable.

In more rural areas, the visibility of an old ROW in aerial imagery is frequently determined by the character of the landscape it crosses and the length of time that has passed since abandonment. Relatively recent abandonments in rural areas are often very easy to follow.

Abandoned Illinois Central segment from Red Bay to Haleyville AL is easily visible between Atwood and Vina, AL, by means of the line of trees growing along the edges of the ROW. Even in forested areas, the nature of the line is different from the surrounding woods and remains obvious. The line was abandoned in 1992, a rather recent abandonment.

Older abandonments, and ones which run through farmland (which is typically reclaimed immediately after abandonment and most traces of the ROW are quickly lost) are harder to pick out, but can still be traced in many cases through use of the historical imagery slider.

Abandoned C&NW ROW a few miles SW of Pilger, Nebraska, is visible in historical imagery running from bottom left to top right. Paths in farmland tend to be much more faint, as there are often no trees on the ROW to mark the line, and the grade has been leveled in order to facilitate easier farming. The transient nature of the typical farmland landscape, with changes in crops and land use, accelerates the masking of railroad remnants. Still, the ROW is still faintly visible even today, as the ballast from the ROW and the stubborn remnants of the grade still provide a light linear mark on the landscape.

Some ROW is turned over for usage in rail-to-trail conversion, and the roads and trails that this creates are frequently marked on Google Earth. One only needs to follow the marked path to trace much of the abandoned ROW, though the trail may deviate from the ROW or follow only a small segment of the rail route.

The Virginia Creeper Trail, built on the Virginia-Carolina Railway ROW, is clearly marked here at its northernmost point in Abingdon, VA.

When roads are built over railroad ROW’s, it is often exceptionally difficult to actually confirm the whole length of such re-use, as grading and paving has removed evidence of the rails that once laid there. However, it is sometimes possible to make a fairly valid guess, based on the curvature of the road and its location relative to other roads in the area. The road will have wide curves and lay fairly level, often parallel to other roads or otherwise located in a manner which is more typical for rails than a road. This type of situation calls for more research than can be ascertained by aerial images only.

Old Railroad Bed Rd in Taft, TN, follows the old NC&StL ROW to Capshaw, AL, removed and turned into a road in the 1930s. The gentle curvature of the road is one of the few indicators that this was once a rail line.

It IS sometimes possible to see where the ROW and the paved roads separate, often depending on topography or population.

Old Tallulah Falls Rwy ROW diverges from the highway built atop parts of its roadbed near Wiley, GA. The ROW is under the highway for much of its length north of this point.

If a road has not been re-profiled or changed significantly since abandonment, there will often be bridges over deep cuts that can’t be explained by natural topography (bridges not over water where there seems to be no reason for a bridge, or a bridge where one might suspect a grading fill would be more appropriate) Occasionally, this can indicate a railway once laid under the road, crossed by the bridge.

Bridge in Tessner, AL, over a deep cut that abandoned Illinois Central ROW runs through. The ROW here is obvious, but had the ROW not run through here, there would be no need for a bridge.

Where a railroad runs (or ran) through very steep topography, the ROW tends to follow waterways, which may be the only relatively level and therefore reasonably gradable land for many miles. Look for signs of possible ROW along such features in areas known to contain abandoned rails. There may also be remnants of bridges crossing the water, then rails continuing on the other side of the water.

Former SOU branch from Parrish to Gorgas, AL, winds along a waterway here. Two wooden trestles are apparent on the left, and a very visible fill can be seen to the bottom right.

While bridges or bridge remnants are not always evident, where rails crossed stagnant water or large bodies of water, remnants of a causeway are often visible for a very long time.

Abandoned ROW on the SW side of Charleston, SC is very visible, with the causeway built to carry the rails over the large area of water still present.

When following linear features not marked as roads or railroads, it’s occasionally difficult to determine what is a power line cut and what is an abandoned ROW. This is rarely an issue though, as power line cuts tend to be much wider and much straighter, and when they deviate from straight, they usually change direction sharply at an angle. ROWs curve much more gradually and are much narrower.

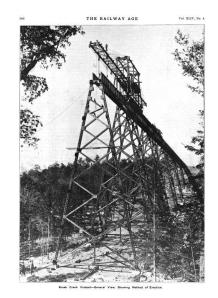

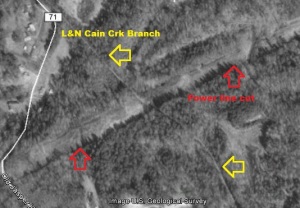

Abandoned L&N Cain Creek Branch near Sayre, AL, crossing a power line cut. Power line cut is much wider and much straighter.

More will be added to this article as I think of more things to add!

A few helpful references for abandoned lines: